Sarrià, the scene of the first ghost goal

In a match between RCD Espanyol and CE Europa, played at Sarrià in 1928, the first "ghost goal" in Spanish football took place. A shot by Manuel Cros was initially awarded, despite doubts about whether it had actually gone in, as the net was broken. After strong protests, led by Zamora, the referee overturned his original decision. Years later, following a similar incident, Cros publicly admitted that the ball had not gone in, thus revealing the truth about one of the most controversial episodes in the history of Catalan football.

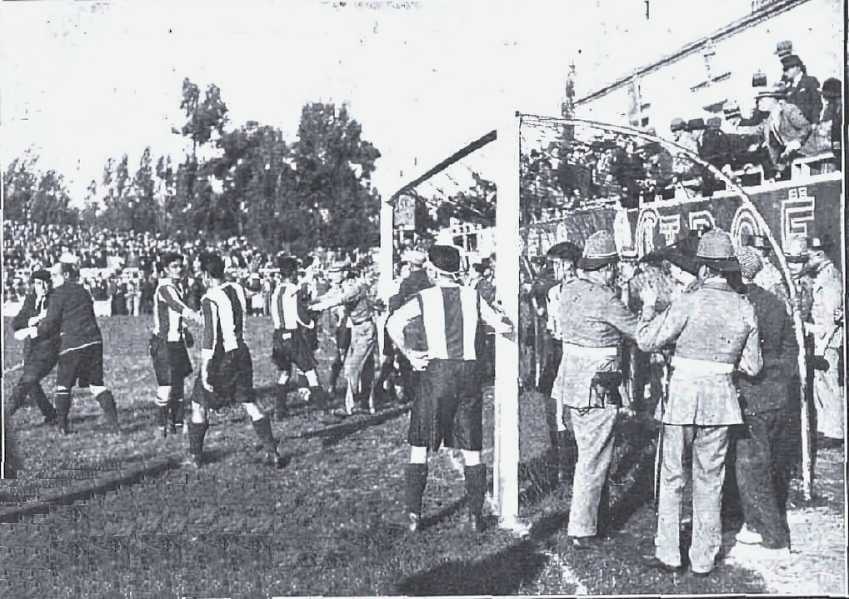

RCD Espanyol and CE Europa faced off at Sarrià on Sunday, October 7, 1928. It was only the second matchday of the recently started 1928–29 Catalan Championship. Highly competitive, the clash between two of Catalonia’s top sides ended goalless (0–0)—a rara avis in an era of exuberant attacking football. The lack of goals, however, wouldn’t stop the match from entering the history books.

Just past the half-hour mark (31st minute), a long clearance caught the home defense off guard and left Cros, Europa’s striker, one-on-one with Saprissa, Espanyol’s last outfield defender. A pure number nine and the attacking reference for the Gràcia-based team, Cros wasn’t exactly a technical marvel, but he charged like a buffalo. That same momentum allowed him to get past the Salvadoran back and face his final obstacle: Zamora.

Confident, the goalkeeper reacted late. When he did, it was too late—Cros beat him with a solid strike. Europa took the lead (0–1) and Cruella, the match referee, clearly validated the goal, pointing to the center circle. Frustrated and aware of his error, Zamora retrieved the ball from inside the net and kicked it angrily to restart the match, but that kickoff never took place. Why?

Cros’s goal came at the South End, next to the Chalet, and from among the spectators on its terrace—just behind the net—came a shout of protest that caught Zamora’s attention. Surprised by such a spontaneous reaction, he asked for the reason, and it had to do with the net: it was torn on the side. Had it already been damaged at the start of the game? Or was it Cros’s shot that caused the tear?

The goal’s validity came into question, and the goalkeeper alerted Cruella to the situation. In front of the goal, with players circling the area, the referee consulted with Just, his goal judge, amid growing tension. His angle of vision wasn’t ideal, as he was on the opposite post from where the ball had supposedly gone in. Still, Just did not hesitate and reaffirmed the goal's legitimacy. That’s when chaos erupted.

Led by Zamora and with unusual vehemence, several Espanyol players confronted the goal judge, roughly shaking him and causing scratches and visible damage to his official blazer. The shameful display incensed the nearby crowd, and a few rowdy fans invaded the pitch to join the altercation. Law enforcement quickly stepped in. There were punches, running, and more than one arrest. Ten minutes of utter disorder turned the South End of Sarrià into a true pandemonium.

Overwhelmed by the situation and once calm had been restored, Cruella reversed his decision and disallowed the goal, ignoring the opinion of his goal judge. That was the final verdict. All of it took place amid Europa’s disbelief, as their opponents remained on the pitch at full strength, despite the deplorable conduct of many of their players.

In the eyes of the fans, Zamora emerged as the winner of the melee. A charismatic player capable of influencing decisions, he saw the torn net as the perfect argument to pressure Cruella. With confusion spreading and the crowd riled up, it was expected that the referee would struggle to uphold the goal. What Zamora didn’t count on was the firm resolve of poor Just. That wasn’t part of his plan. Hence the intimidating fury from him and his teammates.

Sarrià witnessed something unprecedented: the first ghost goal in Spanish football—or at least the most talked-about until that time. “The Cros Case", as the controversial episode came to be known, stirred significant uproar, and for a time, goal judges ceased to operate in their traditional role.

The seriousness of the incident forced the Catalan Football Federation’s Competition Committee to take action. Zamora and the Tena brothers, all Espanyol players, were handed a three-week suspension. The punishment was later reduced to one week.

Even though the goal wasn’t validated, the question remained: did Cros’s shot truly cross the line? The mystery would take more than five years to be resolved, and it was the player himself who would finally shed light on the controversial incident. This would only happen thanks to another ghost goal—this one in Madrid’s old Chamartín stadium, during a match between Real Madrid and Espanyol on December 31, 1933.

The match ended in a 3–2 win for the hosts but was clouded by controversy. With Madrid leading 2–1 just before halftime, a long-range shot from “Tin” Bosch clearly beat goalkeeper Cayol. The shot—powerful, diagonal, and rising—flew past the Canarian keeper but, surprisingly, the ball didn’t remain in the goal. Instead, it ended up in the hands of a spectator behind it. What had happened?

Espanyol celebrated wildly what they saw as the 2–2 equalizer, claiming that the ball had torn through the net and—due to its diagonal trajectory—landed in the stands. Naturally, Real Madrid players disagreed, and chaos ensued near Cayol’s goal. Some fans caused disturbances, police had to intervene, and the goal judge opted out of the decision. In such a scenario, referee Del Campo Echevarría ruled it out. No one, he argued, could confirm the goal. A scene uncannily similar to that October day in 1928 at Sarrià.

The incident was widely covered in both Madrid and Catalan press. The latter, in particular, drew parallels to the famous Espanyol–Europa match of 1928. The occasion called for an interview with Manuel Cros—or even Ricardo Zamora himself—two of the protagonists of that earlier event. Mundo Deportivo rose to the occasion and interviewed Cros.

The interview, penned by Phil de Escocia (a pseudonym for journalist Juan Fina), was published in the January 6, 1934 edition of the Barcelona daily. Cros, who curiously was playing for Espanyol during the 1933–34 season, had this to say when asked about that controversial goal at Sarrià, back when he wore Europa’s jersey:

- “The Sarrià goal wasn’t a goal. I already told you that, and I repeat it. I’ve never said otherwise when asked.”

- “Then how did it all unfold?”

- “You saw it. They made it up, and they solved it. My role was limited to taking the shot… and giving myself away. When I saw the ball hadn’t gone between the posts and under the crossbar, I put my hands on my head and grabbed my hair... that 'Cros haircut'—brush-style—that was in fashion back then."

- "Exactly," says Cros, smoothing his now elegantly parted hair. “As I said, I gave myself away. Saprissa, smart and a true sportsman, came to me and said: ‘You’re a sportsman and a gentleman—you won’t deny that wasn’t a goal.’ I simply told him that it wasn’t appropriate for me to intervene unless asked by someone with authority. If that happened, I’d tell the truth, as always. So I stepped away from the commotion, the tugging on blazers with piping, the tricorne hats, and that Civil Guard officer with the red cap who was the first to point out the referee’s mistake—along with most of the crowd and nearly all of you.”

They say one nail drives out another, and five years later—thanks to another ghost goal—Cros publicly clarified what had happened on the pitch at Sarrià on October 7, 1928.

During the 1920s, Europa emerged as a genuine challenger to the dominance of Barça and Espanyol in the Catalan Championship. Manuel Cros, their striker, was the attacking symbol of that remarkable team. Later, he would go on to wear Espanyol’s blue and white in two separate stints.

His statements to Mundo Deportivo coincided with the first of those spells (1933–34 season). Already in the twilight of his career, Cros played a secondary role, rarely featuring in the plans of manager Ramón Trabal, who only gave him a couple of official appearances before transferring him to CE Sabadell (Second Division) in early February 1934.

Oriol Pagès Rosique

HISTORICAL RESEARCH GROUP OF THE RCD ESPANYOL FOUNDATION